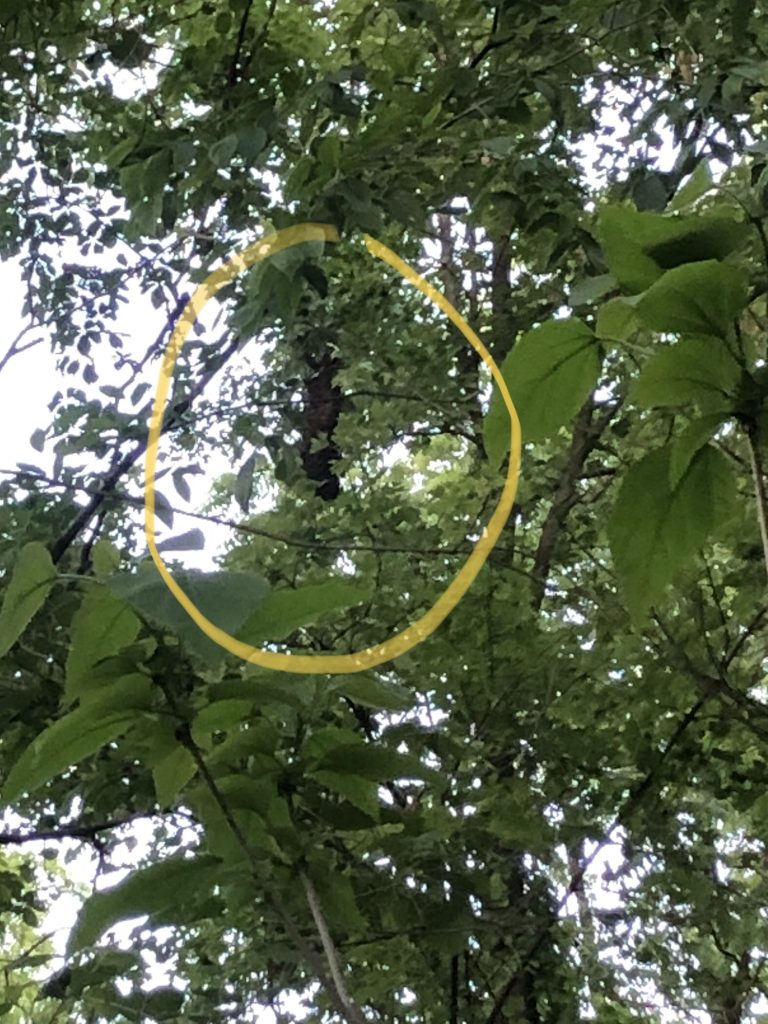

Honeybee swarms are a somewhat common sight in the spring, though admittedly I didn’t pay too much attention to them until I started researching beekeeping. Often, when we see a giant undulating mass of honeybees hanging on a tree limb or car mirror, our initial reaction is fear because bees = pain (and in the case of those of us who grew up in the 90’s, we were traumatized by the beginning of My Girl).

But when bees swarm, they are typically very unlikely to sting you because their sole purpose at that time is to find a suitable new home and protect the queen.

To understand why they swarm, let’s briefly go over roles in the hive. Of course we’ve all heard about the queen bee – she’s the one who lays all of the eggs to produce all of the thousands of bees in the colony. The majority of the bees in a colony are the (all female) worker bees – they do most of the work, and their job in the colony is determined by how old the are. As an interesting side note, worker bees typically only live about 3 weeks in the summer but 3-4 months in the winter – and this is caused by the queen actually laying a different type of egg in preparation of winter. Replacing the workers less often helps conserve energy and resources. Then finally there are the (male) drone bees – they are unable to sting, do not produce honey, and are unable to even feed themselves (instead relying on the worker bees to keep them alive). The drone’s sole purpose is to mate with a virgin queen on her mating flight (which only occurs once in the queen’s life). After mating, the drones die.

A colony of bees, while being made up of individual bees, is considered a superorganism – the individual bees cannot survive on their own for extended periods and so the colony essentially acts as one large composite organism. While the queen bee lays eggs to produce baby bees, the way a colony of bees reproduces is by dividing and swarming.

When they swarm, the original queen leaves the hive with roughly half or so of the worker bees (drones generally do not join the swarm) to go find a new home. Meanwhile, in the original hive, a new queen emerges from the distinctly peanut shaped queen cells. There are often several queen cells produced, and whoever emerges first will destroy the other queen cells or literally fight to the death until one queen is left standing. At this stage, the queen is still fairly useless as a virgin queen can only lay eggs that produce drones, which would quickly cause the colony’s demise by lack of useful worker bees. So the queen leaves on a mating flight and after successfully mating with several drones from outside of her own colony, she will return to the hive and is now able to begin laying fertilized eggs that will develop into worker bees.

Experienced beekeepers can see signs of a colony preparing to swarm. They are able to divide the colony themselves if they want by mimicking a swarming event – basically catching the queen in a special queen cage clip and placing her with a portion of worker bees (and preferably a couple of frames of honey & brood) in another hive body. The worker bees do not want to leave the queen, and if there is already honey and brood in the new hive box, they are much more likely to just stay put rather than flying off to find something else. And voila, you just saved yourself about $200 worth of bees.

In summary – honeybees swarm to reproduce by dividing their colony. You do not need to be fearful of a swarm, and you don’t need to do anything about them (unless you know of a local beekeeper that might want to try to catch the swarm, in which case – call them quickly!). Honeybee swarms will generally move on fairly quickly and be gone within a few hours to a day. So the next time you see a swarm, enjoy the show from a distance, they’ll be on their way soon enough!